The Greatest Intellectual Achievement of the human race is arguably the Standard Model of Elementary Particles. The Standard Model consists of Special Relativity, Quantum Physics, Noether’s theorem and gauge theories, Quantum Electrodynamics, Quantum Chromodynamics, and a framework for all elementary particles, and more. It is a towering achievement of physics that was created by thousands of geniuses over a period of several decades. It is the theory of almost everything.

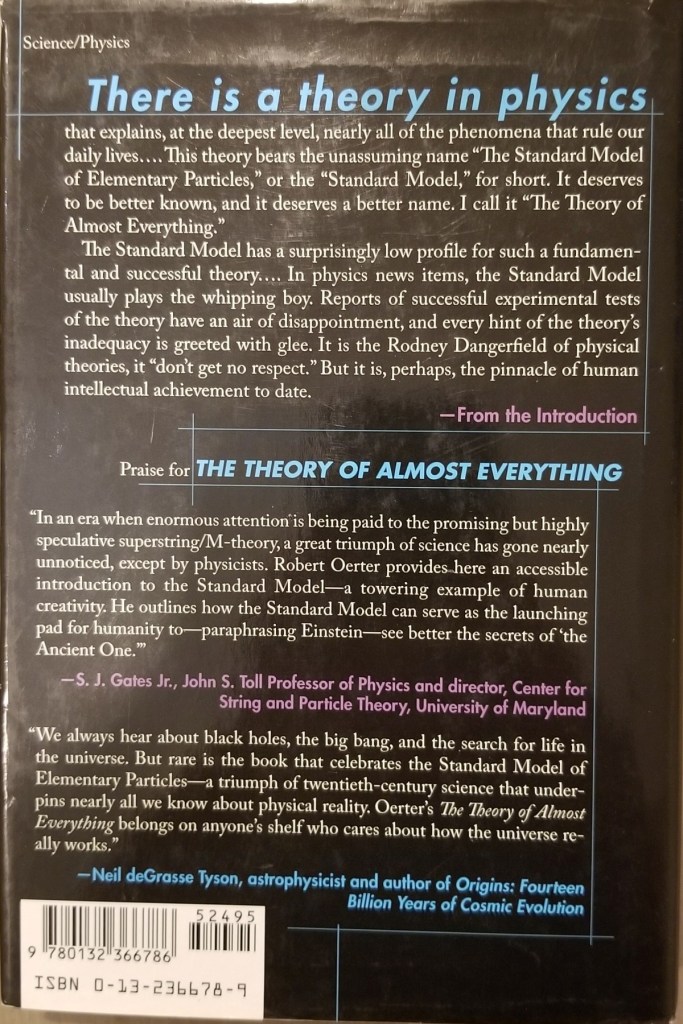

Despite that fact it is not getting a lot of respect. Everyone is just trying to find something wrong with it. The reason is that as soon as it was created people realized that something was wrong with it. It could not be reconciled with General Relativity. Something was missing. So, finding out what is wrong with it or what is missing has been a top priority for physics for several decades. The book “The Theory of Almost Everything” by Robert Oerter is a very interesting book covering the standard model, its components, its history, and what could be missing. It contains a few formulas but other than that it is mostly readable to laymen.

Book Formats for The Theory of Almost Everything

The Theory of Almost Everything: The Standard Model, the Unsung Triumph of Modern Physics by Robert Oerter comes in three formats. I bought the hardback format.

- Hardcover – Pi Press (July 22, 2005), ISBN-10 : 0132366789, ISBN-13 : 978-0132366786, 336 pages, item weight : 1.2 pounds, dimensions : 6.37 x 1.11 x 9.3 inches, it costs $35.08 on US Amazon. Click here to order it from Amazon.com.

- Paperback – Penguin Publishing Group (September 26, 2006), ISBN-10 : 0452287863, ISBN-13 : 978-0452287860, 336 pages, item weight : 10.8 ounces, dimensions : 5.51 x 0.81 x 8.34 inches, it costs $16.99 on US Amazon. Click here to order it from Amazon.com.

- Kindle – Publisher : Plume (September 26, 2006), ASIN : B002LLCHV6, ISBN-13 : 978-1101126745, 348 pages, it costs $6.99 on US Amazon. Click here to order it from Amazon.com.

Amazon’s Description of The Theory of Almost Everything

There are two scientific theories that, taken together, explain the entire universe. The first, which describes the force of gravity, is widely known: Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity. But the theory that explains everything else—the Standard Model of Elementary Particles—is virtually unknown among the general public.

In The Theory of Almost Everything, Robert Oerter shows how what were once thought to be separate forces of nature were combined into a single theory by some of the most brilliant minds of the twentieth century. Rich with accessible analogies and lucid prose, The Theory of Almost Everything celebrates a heretofore unsung achievement in human knowledge—and reveals the sublime structure that underlies the world as we know it.

My five-star Amazon review for The Theory of Almost Everything

Below is my full length giant review of The Theory of Almost Everything. Unless you are really interested, I suggest you read the somewhat shorter Amazon version by clicking the link above.

An introduction to the greatest intellectual achievement of the Human Race

The public has to a large extent missed the greatest scientific revolution in the history of the human race because mainstream media has largely ignored this breakthrough, despite the fact that the Nobel Prize committee has been raining Nobel Prizes over it. In the 1970’s a theory that explained, at the deepest level, nearly all of the phenomena that rule our daily lives came into existence. The theory called “The Standard Model of Elementary Particles” is a set of “Relativistic Quantum Field Theories” that explains how elementary particles behave, which elementary particles there are, and why they have the properties they have, for example, isospin, spin, charge, color charge, flavor, even mass, or mass relations in many cases.

The theory explains how all of the fundamental forces in nature work except gravity. The theory describes how the elementary particles interact; decay, how long they are expected to exist, and how they combine into other subatomic particles. The theory uses only 18 adjustable parameters to accomplish all of this.

In the extension the theory thus explains how nucleons and atoms are formed and what properties the atoms will have, and how molecules will form and what properties molecules will have, their chemical reactions, and what elasticity, electric conductivity, heat conductivity, color, hardness, texture, etc. any material will possess. In the extension it explains why mass and matter exist, how the sun and the stars work, and the theory is therefore the ultimate basis of all other science. It also provides a formula, or an equation of almost everything.

Best of all it has been thoroughly verified experimentally, in fact the predictions the theory has made have been confirmed with such stunning accuracy and precision that it could be considered the most successful scientific theory ever. A theory that successfully unites all physics and basically all of human knowledge of the Universe into one single theory has never before existed.

However, “The Standard Model” does not incorporate gravity and the general theory of relativity, and cannot explain dark energy, dark matter and why neutrinos have mass. Therefore, almost as soon as the theory came into existence physicists started looking for the next theory that would finish what the “The Standard Model” did not finish.

Example of such theories are GUT theories, SO(5), SO(10), string theories (abandoned), super string theories, and M-theories. Even though those new theories are extremely interesting they have not been verified or able to predict anything. In comparison with the “Standard Model”; super string theories, grand unified theories, chaos theories, you name it, are essentially nothing, but are still better known. Hopefully this will change in the future, either because the Standard Model gets the respect it deserves, or because a more complete theory can be verified.

About the book

This book explains to the layman what the “Standard Model” is and how it came into existence. The book is by no means a perfect book. I think there are several problems with the book. However, I decided not to take off any star because there are very few books written for science interested non-physicists that explain the “Standard Model of Elementary Particles”. Dr. Oerter deserves five stars just for his decent attempt at doing so. I find Dr. Oerter to be a good writer and popularizer. I don’t think he is as good as Isaac Asimov, or Carl Sagan, but close, and he is writing on a much more complex topic then, for example, Carl Sagan did.

I studied physics as an engineering student, and I could understand most of text (but not every detail regarding everything). However, I believe anyone who is somewhat familiar with science, especially physics and math, can understand most of this book. For me more diagrams and more equations would have helped. For readers without much background in physics more and better diagrams would definitely have helped. Dr. Oerter came close to writing a good book for the layman, but the book was still lacking in certain aspects. In the remainder of the review, I will give a brief synopsis for each chapter and present my opinions and reflections on each chapter. In a sense I have written a short review for every chapter. My intent is to both tell you what the book is about and give my opinions on the different sections of the book.

Chapter 1: The first unifications

In Chapter one Oerter gives an interesting overview of the history of physics. Physics has typically been divided up into many fields. New discoveries have led to either new sub disciplines or the merging of existing sub disciplines (unifications). Nineteenth century physics was divided into many sub disciplines.

Dynamics (the laws of motion)

Thermodynamics (the laws of temperature, heat and energy)

Waves (oscillations in water, air, and solids)

Optics

Electricity

Magnetism

However, because of the atomic hypothesis, thermodynamics and wave mechanics were swallowed up by dynamics. For example, temperature and heat were now explained in terms of atomic and molecular motion. The theory of electromagnetic fields subsumed optics, electricity, and magnetism (light is an electromagnetic wave). All of physics, it seemed, could be explained in terms of particles (atoms) and fields. New discoveries would alter the picture once again and the old field theories had to be abandoned, and the laws of classical mechanics (dynamics) had to be altered.

Finally, the physicists were able to come up with a unified theory that explained almost all of physics and in the extension all of science, the standard model of elementary particles. This chapter was very basic and not difficult to understand. I think his approach to give an overview of physics was both unique and enlightening. His description of how physics and our understanding of the Universe went through periods when our knowledge expanded and gave rise to new fields and due to new discoveries, that led to a deeper understanding resulted in the merging of these fields. So, in summary more knowledge lead to more fields, then deeper understanding united them. This went back and forth a few times. Finally, we have a unified theory of almost everything, the Standard Model (if we exclude the General theory of relativity).

Chapter 2: Einstein’s relativity and Noether’s theorem

Even though the book is a Physics book, I think it is also a book on Philosophy. The way I see it Physics is in a sense both Science and Philosophy, the kind of Philosophy that can be falsified, verified and proven wrong or correct. Let me explain what I mean by telling you about Noether’s theorem. Noether’s theorem states that whenever a theory is invariant under a continuous symmetry, there will be a conserved quantity. As an example of what a continuous symmetry is, is the following: any physical experiment that is performed at a certain time will have the same result if it is performed exactly the same way a certain time later. That seemingly self-evident observation means that Energy is conserved.

Another example is any physical experiment that is performed at a certain place will have the same result if it is performed exactly the same way somewhere else. That seemingly self-evident observation means that momentum is conserved. Let me add that “exactly the same way” really means that! Gravity, other forces, differences in light, or anything else cannot be different in the second experiment. The only thing allowed to be different is the position “x” (if that is our symmetry variable). That is what a continuous symmetry means, changing just one thing, and everything stays the same.

Noether’s theorem has been the guiding principle behind the standard model, and it is used to find conservation laws where symmetries are found, and it is used to find symmetries where conservation laws are found. It is a spontaneous symmetry brake that allows the Higgs Boson to give all other particles their mass (excepting mass less particles). This is the reason that matter and everything in our Universe exists. The Higgs Boson is also called the God particle. So, Noether’s theorem is both very useful in a practical sense and deeply philosophical at the same time. In addition to Noether’s theorem the standard model is built upon the special theory of relativity and a modern formulation of quantum mechanics (Quantum field theory), QED, QCD, as well as some discoveries regarding elementary particles. I can add that Noether’s theorem was formulated by a Jewish woman, Emmily Noether, who could not get a job in academia because she was a woman. This theorem is one of those very important but mostly unknown discoveries, like the invention of paper by the Chinese Tsai Lun.

Oerter does not attempt to explain the special theory of relativity; however, he tries to give the reader an idea of what it is. The problem with his approach is that he gives the reader just enough information to enable the observant reader to come up with the apparent paradoxes within the special theory of relativity, but not enough information to help the reader to easily resolve them. He also confuses the reader by not distinguishing between rest mass and relativistic mass. The observant reader will think that he is contradicting himself. The term relativistic mass is the total mass and the total quantity of energy in a body. The rest-mass is the mass of the body when it is not moving. The formula E = mc^2 is always true, when it refers to relativistic mass, which is why we talk about an energy/mass equivalence. The other more complex formula Oerter presents refers to rest mass. There is no such thing as an energy/rest mass equivalence (except at speed 0) but that is what the reader who is not already familiar with the subject will end up believing.

Another mistake Oerter does is in regard to the fact that the speed of clocks will be measured differently in different reference frames. On page 35 last paragraph Oerter writes “Here, we have an apparent paradox: If each reference frame sees the other as slowed down, whose clock will be ahead when the passengers leave the train?” Then he implies that the paradox has to be solved by incorporating the General theory of relativity. Even though that may be how it was first solved, you can solve this form of the so called “Twin Paradox” and other similar paradoxes from within the framework of the special theory of relativity itself. So even though I enjoyed reading about Nother’s theorem and still think this chapter could use some improvement.

Chapter 3: (The End of the World as we know it) + Chapter 4: (Improbabilities)

Oerter explains Quantum Physics in a very typical manner, and he mostly avoids making it look weirder than it actually is which he should be commended for (that is not true for every author). However, there is one thing that all Physicists seem to do when they explain Quantum Physics to the layman which annoys me greatly. The matter waves (or quantum fields) in Quantum Physics are quite strange entities. The reason they are so strange is because they do not exist in a real sense, they are more correctly stated mathematical abstractions. Oerter states this clearly, which is good.

However, he then goes on to mention De Witts’ idea about multiple Universes without acknowledging that these “bizarre solutions” to various Quantum Wave conundrums are completely unnecessary. So, to some extent he is still making Quantum Physics appear weirder then it is (but I have seen worse). Well, OK, Quantum Physics is weird, but we don’t need to make it seem even weirder.

After giving a background to the special theory of relativity and Quantum Physics, Oerter continues explaining relativistic Quantum Physics including the fantastic prediction you get when you combine the special theory of relativity with Quantum Physics; that for every particle there is a twin particle with exactly the same mass, and spin, but opposite charge and isospin. These particles were called anti-particles and until they were actually found physicists tried to get rid of them from the theory. However, the combination of the special theory of relativity and Quantum Physics would lead not only to much better explanation for such things as the radiation and light spectrum and the properties of atoms, it would also lead to new discoveries. This is what is referred to as Relativistic Quantum Mechanics.

Chapter 5: The Bizarre Reality of QED

Richard Feynman came up with a new representation of relativistic quantum physics for electrons that did not use waves, called Quantum Electro Dynamics (QED). This was one of the first steps towards the standard model. Instead of viewing electrons as particles governed by waves, Feynman viewed electrons as particles guided by fields consisting of all possible paths and their probabilities. He used the two-slit experiment as a guide when formulating the equations for the probabilities of the paths for the electrons (and in the extension may other particles). When he summed up all the possible paths and compared with the old Quantum Mechanics (Wave Mechanics) he got the same answer as Quantum Mechanics in every case. In fact, his new approach was able to explain and calculate phenomena’s like the electrons spin and the fine structure constant that Quantum Mechanics (Wave Mechanics) could not explain properly, and his approach also would prove crucial for the development of Relativistic Quantum Field Theory.

So, in summary, first came Quantum Mechanics, then Relativistic Quantum Mechanics, and then QED and Relativistic Quantum Field Theory. I can add that this chapter also explains Feynman diagrams and an infinity problem that cropped up. The three infinities that cropped up corresponded to the electron’s mass, the photon’s mass, and the electron’s charge. However, the problems with these infinitives were solved using a normalization process that is also explained in this chapter. I can add that I think QED probably seems less strange to laymen then Wave Mechanics because it is easier to visualize the probabilities of possible paths as compared to waves that do not even exist, even though their “amplitude squares” represents something real. This chapter was probably one of the harder chapters to understand (for those who know nothing about QED). This chapter could really have been made better by using many more diagrams and figures. Again, I am not going to knock a star for that because the book is overall so unique and important.

Chapter 6: Feynman Particles, Schwinger Fields

Chapter 6 was a short but interesting chapter. Julian Schwinger took a different approach to QED than Feynman; he sorts of invented a new wave mechanics, in which a quantum field can be pictured as a quantum harmonic oscillator at each point in space. Even though the two approaches used different models Freeman Dyson proved in 1949 that Schwinger’s field theory point of view and Feynman’s sum-over-all-paths approach were in practice identical. However, the two approaches are useful for different things and form the basis of Quantum Field Theory. QED and Quantum Field Theory eliminate the distinction of particle and field and in a sense removed the conundrum of the particle and wave duality. In the nineteenth century light was an electromagnetic wave (well it still is) and in the old Quantum Physics it was both a wave and a particle, however, in Relativistic Quantum Field Theory it is something completely new-a quantum field, neither a particle nor a wave, but an entity with the aspects of both.

Chapter 7: Welcome to the Subatomic Zoo

In this chapter Oerter describes the history of the “strong nuclear force” and the “weak nuclear force” and the subatomic zoo that later emerged. There are four fundamental forces of nature, electromagnetism, gravity, and the “strong nuclear force” and the “weak nuclear force”. The two latter fundamental forces were not known until the 1930’s. The studies of these two new forces led to the predictions and discoveries of new elementary particles. One of these was the pion, however, when the physicists looked for this particle in the cosmic background radiation, they found an elementary particle that was similar to the pion but had the wrong mass.

After some confusion it became clear that it was not a pion but a new never foreseen particle that was named the meson. This was a problem because it was a new entity which the existing physics theories could not explain. However, it got worse. More elementary particles were discovered in the 1940’s 1950’s and the 1960’s. Our Universe turned out to be a lot stranger than people thought, and people started talking about the subatomic zoo. These newly discovered elementary would remain big mysteries until the event of the Standard Model in 1974. This chapter was pretty straight forward and easy to understand. Oerter does an excellent job in making this history interesting and entertaining to the reader and the chapter also contains some humor.

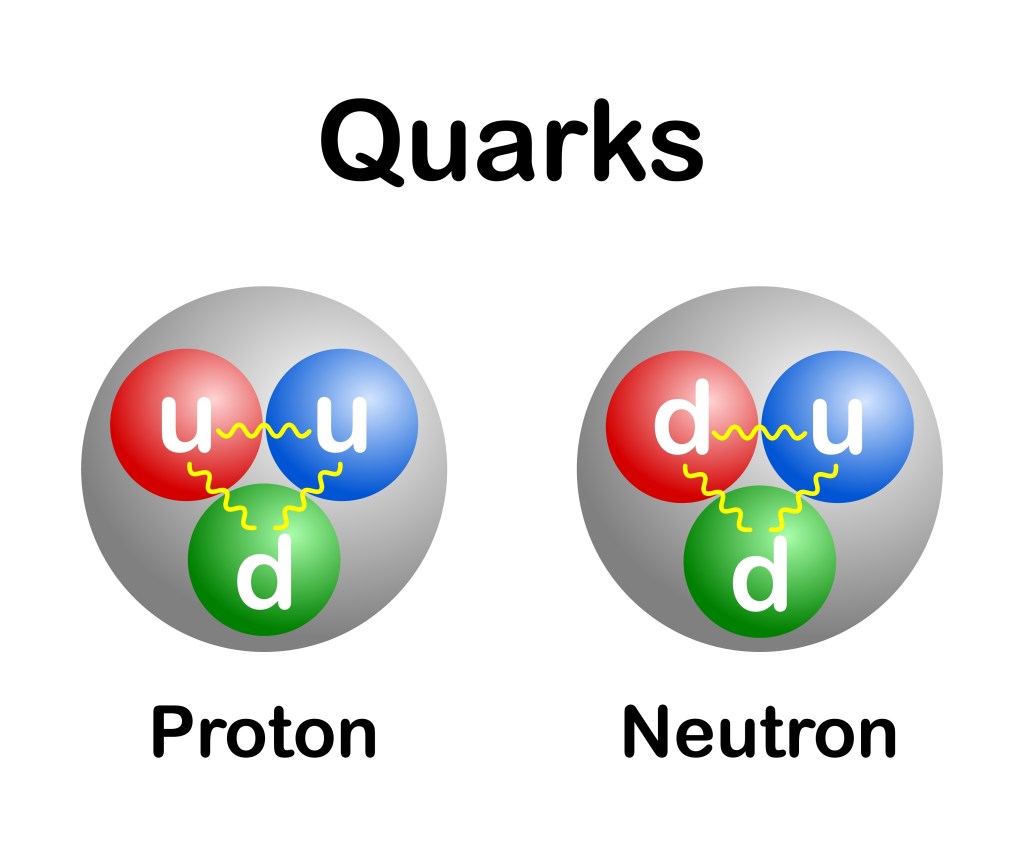

Chapter 8: The Color of Quarks

In the 1960’s physics had become ugly because of the subatomic zoo. Murray Gell-Mann and Yuval Neeman suggested a periodic table for elementary particles (like there is a periodic table for the elements). This periodic table was referred to the eightfold way. The eightfold way was also referred to as the SU(3) theory. It led to the discovery of an elementary particle that was even more fundamental than the known elementary particles, the Quark. It was soon established that there were two kinds of fundamental elementary particles: leptons and Quarks, in addition to the Bosons. Let me explain the details. There are elementary particles with whole number spin, and they are called Boson’s, and there are elementary particles with half number spin called Fermions.

The Pauli Exclusion Principle (that no two particles can occupy the same state) applies to Fermions but not to Bosons and therefore the two different types of particles behave very differently and follow different kinds of statistical rules (Bose-Einstein statistics versus Fermi-Dirac statistics). All force carriers are Boson’s while some Fermions are used to build “normal matter”. Examples of Bosons are the photon, gluons, W and Z Boson, mesons, the Higgs Boson (the God particle). The Fermions come in three families, each with four particles and their anti-particle.

Electron / positron

Neutrino / anti-neutrino

Up quark / anti up quark

Down quark / anti down quark

muon / anti-muon

Mu Neutrino / anti-mu-neutrino

Charm quark / anti charm quark

Strange quark / anti strange quark

tau / anti-tau

Tau Neutrino / anti-tau-neutrino

Top quark / anti top quark

Bottom quark / anti bottom quark

The quarks can be used to build other particles, but leptons cannot. For example, a quark and an anti-quark pair form a particle called a meson (there are many kinds of mesons). A triplet of quarks is called a Baryon. An example of a baryon is the proton which consists of two up quarks and one down quark. Another example is the neutron which consists of one up quark and two down quarks. So just like electrons, protons and neutrons build atoms; the quarks build other elementary particles, for example, protons. As mentioned, the six flavors of Quarks are up, down, strange, charm, top and bottom.

However, the Quarks also have colors (well they are not real colors), red, blue and green which sort of correspond to the three kinds of charges for the strong nuclear force. Based on this new model a new Quantum Field Theory called Quantum-Chromodynamics (QCD) was created which together with QED would form the basis of “The Standard Model of Elementary Particles”. This was also a very straight forward chapter that was both interesting and not very difficult to understand. Again, Oerter makes the story interesting and captivating. This is perhaps the most interesting chapter in the book.

To learn more about Protons, Neutrons, Quarks, Gluons, Color Charges, and Quantum Chromodynamics you can watch this 10 minute video below.

Chapter 9: The Weakest Link

Despite the eightfold way, the Quarks, QED and QCD, all was still not well. The Weak Nuclear force was still not fully understood. Martinus Veltman, Steven Weinberg, Abdus Salam, and Sheldon Glashow were the people chiefly responsible for developing a theory for the weak nuclear force. It involved W+, W- and Z0 Bosons and something called spontaneous symmetry breaking.

These theories in turn led to something called the Higgs field and the so called Higgs particle or Higgs Boson (named after Peter Higgs who first introduced the concept of spontaneous symmetry breaking in elementary particle theory). The Higgs particle provided the physics community with a very nice surprise. The Higgs particle gives electrons (and other leptons) and the Quarks their mass. Unexpectedly we thus got an explanation as to why many elementary particles have mass and therefore why matter exists. This is why the Higgs Boson is often referred to as the God particle. It just showed up because of the theories explaining the weak force and turned out to be what created our Universe by giving the elementary particles their mass.

There was just one problem. The Higgs Boson had not yet been found when this book was written. Once the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) came online it became possible to find the Higgs Boson. This final touch to the Standard Model was the one that was the most difficult to grasp. I had a hard time understanding what spontaneous symmetry break really was, and the Mexican hat potential, etc. I think that Oerter needs to look over this chapter and find a different approach to explaining spontaneous symmetry break. I think that Oerter actually sorts of “gave up” at this point. This topic is too abstract for the layman so instead of making a good effort explaining spontaneous symmetry.

Chapter 10: The Standard Model at Last

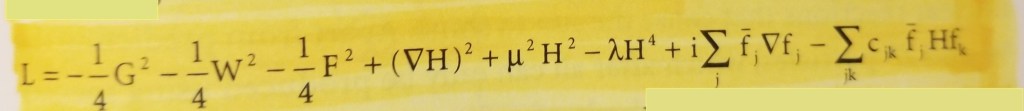

The standard model is built from relativistic quantum field theory, specifically QED and QCD. In chapter 9 QED was incorporated into electroweak theory which led to the Higgs Boson etc. QED is interwoven together with QCD to create a single theory whose essential elements can be written in a single equation.

Yes, that is right; an equation of everything, or almost everything. This equation is stated on 207 in this chapter. The equation over all equations that there ever was. You should buy this book just to look at it.

The equation of everything is not as complicated as you may think. It is a Lagrangian function that summarizes all propagators and interactions, and it contains 18 adjustable numerical parameters. I admit that I don’t understand the equation fully, but Oerter explains the parameters and as mentioned it is just a big Lagrange function. As Oerter states “this equation is the simplicity at the bottom of it all, the ultimate source of all complex behavior that we see in the physical world; atoms, molecules, solids, liquids, gases, rocks, plants and animals”.

Oerter also discusses the birth of the Universe in the context of the Standard Model. In my opinion this was a very cool chapter, and Oerter does a good job at exciting the reader in this chapter. Naturally the equation of everything is a little bit difficult to understand and if you don’t know what a differential equation is you can forget about it. However, understanding the equation of everything is not important. The main point of this chapter is that there is such an equation.

Chapter 11: The Edge of Physics, Chapter 12: New Dimensions

As Oerter states in chapter 11 “The standard model is by far the most successful scientific theory ever. Not only have some of its predictions been confirmed to spectacular precision, one part in 10 billion for the electron magnetic moment, but the range of application of the theory is unparalleled. From the behavior of quarks inside the proton to the behavior of galactic magnetic fields, the Standard Model works across the entire range of human experience. Accomplishing this with merely 18 adjustable parameters is an unprecedented accomplishment, making the Standard Model truly a capstone of twentieth-century science.” However, this is not the end of physics. Gravity is explained by the General Theory of Relativity but is not incorporated into the Standard Model.

There is also dark matter and dark energy which is not part of the Standard Model. The neutrinos seem to have mass; however, they are predicted to have no mass in the Standard Model. In addition, it would be nicer to have fewer adjustable parameters than 18. Is there may be a better theory? In chapter 12 Oerter is discussing Grand Unified Theories (GUT), or SO(5) and SO(10) theories as well as super string theories, and M-theories. These are theories that might be able to do everything the Standard Model can do plus what it cannot do. However, none of these theories have ever predicted anything, so unlike the Standard Model they are speculation. There is some controversy regarding these issues, and I think Oerter might have been a tiny bit biased against super string theory here. However, he still explains what super string theory is about pretty well.

Final Conclusion and Recommendation

I highly recommend this book for anyone who wants to understand something about our world and the Universe. However, don’t expect to understand everything, it is not written so that you can. I wish Physicists would become a little better at explaining these matters to the layman using nice descriptive pictures and a little bit of math too (don’t assume math is always bad). I once read a 30 page long Swedish book on the special theory of relativity that successfully explained the kinematics, dynamics, and magnetism in relativity to your average high school kid. The Lorenz transforms, formulas for acceleration, E = mc² and magnetism were derived using simple algebra and a tiny bit of calculus at one point. That is the way these kinds of books should be written, but I have seen this only once in my life. Excluding this single example (the Swedish book), Oerter’s book is one of the best books on Physics for the layman that I have ever read.

Here are some other posts that are related to the content of this book.

- The Speed of Light In Vacuum Is a Universal Constant

- Two events may be simultaneous for some but not for others

- Every Symmetry is Associated with a Conservation Law

- Time Dilation Goes Both Ways

- The Pole-Barn Paradox and Solution

- Time is a Fourth Dimension

- Electric Charge is not the only type of Fundamental Charge