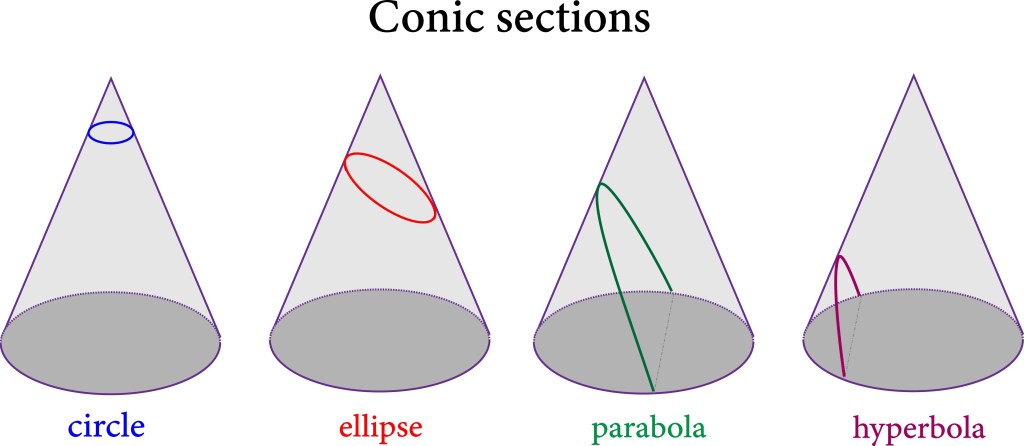

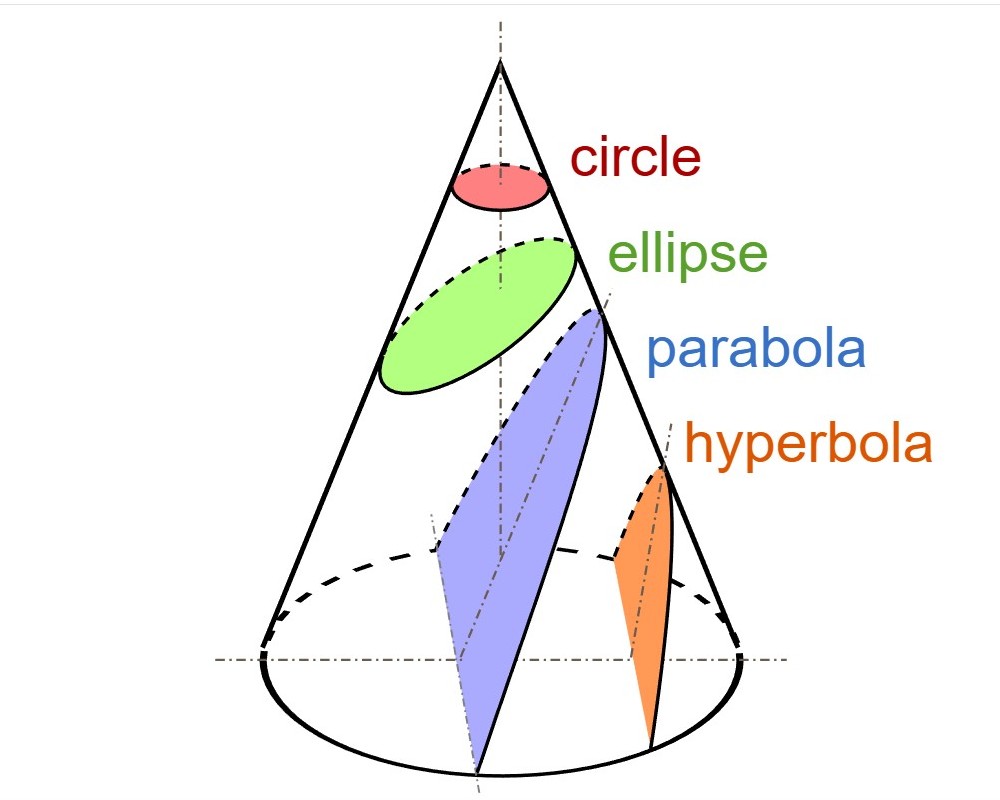

Super fact 80 : A conic section is a shape formed by slicing a cone with a plane. There are four such shapes, circle, ellipse, parabola, and hyperbola. The conic sections universally describe motion under gravity. The orbits of planets around their stars are circles or ellipses, comets fly around space in elliptical orbits, or parabolic or hyperbolic paths. Objects thrown up in the air follow parabolic paths. They are the basis for a huge amount of engineering applications.

Esther’s writing prompt: January 21 : Shapes

Click here or here to join in.

The four conic sections, circle, ellipse, parabola and hyperbola are fundamental and very useful shapes in mathematics, physics and engineering. Well, a circle is a special case of an ellipse, so it is really only three conic sections. The motion of the planets and other stellar objects are described by the conic shapes. Isaac Newton derived his law of gravitation from Kepler’s laws, which describe planetary orbits as ellipses.

The conic sections are all described by second degree equations (quadratic equations) and are in that sense the simplest shapes aside from points and lines. It is important to understand that there is an infinite amount of shapes that are almost conic sections and look like conic sections, but it is the exact mathematical properties of the four conic sections that make them so common in physics, mathematics, nature and engineering.

It may not come as a surprise that the circle is a fundamental and important shape, but I believe that the fact that the other conic sections are also fundamental in mathematics, physics and engineering come as a surprise to people outside of the STEM fields. It is a true and an important fact regarding how our world works.

Conic Sections

As mentioned, the conic sections are fundamental shapes that appear in a lot of places in STEM. Below are a few examples.

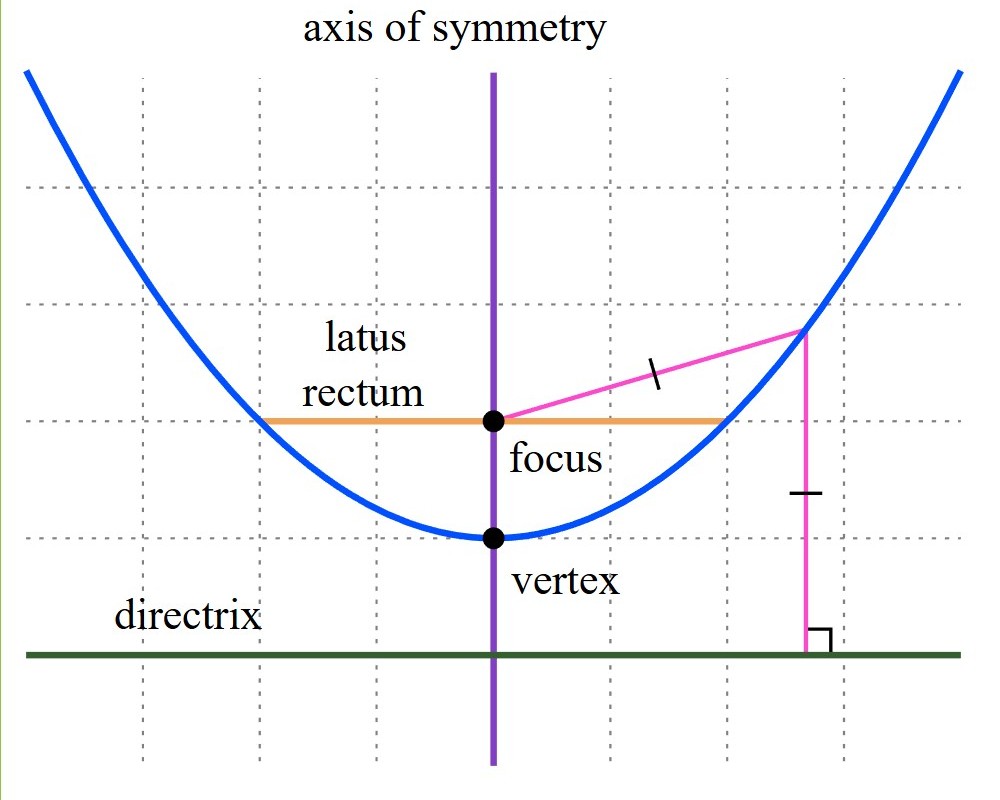

Parabola

A parabola is formed when a plane cuts a cone, so the plane is parallel to a side of the cone. Parabolas are shapes that are roughly U-shaped and described by the equation y = x^2 or more generally by y = ax^2 + bx + c. Parabolas have a so called focus point. See the picture below. If you throw a ball, or any object, up in the air its trajectory will be a parabola (ignoring distortions caused by friction and wind). I should say the parabola you get in this case is upside down. The parabola is important when you design any kind of projectile.

Antennas shaped like parabolas (in 3D) will direct incoming radiation and waves towards their focus point. If the surface is reflective a light located at the focus point will reflect to create a straight beam. Parabolas are used for radio telescopes, satellite dishes, car headlights, flashlights, solar cookers, solar power plants, water fountains, suspension bridges, business modelling and thousands of engineering applications. Parabolas like circles and the other conic sections shape our modern world (pun intended).

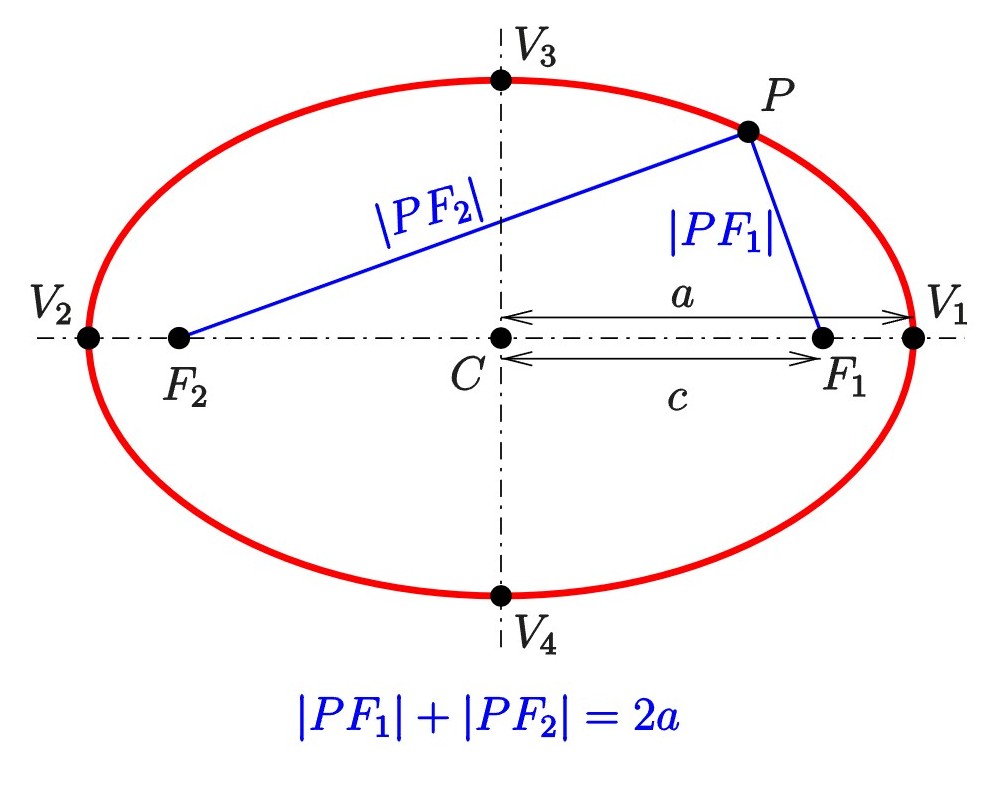

Ellipse and circle

As mentioned, a circle and an ellipse are conic sections formed by intersecting a plane with a cone. You get a circle when the cuts perpendicular to the cone’s axis (see pictures above) and an ellipse form when the plane intersects the cone at a slant but not slanted so much that it becomes a parabola or a hyperbola. An alternative for an ellipse is that the sum of the distances from any point on the curve to two fixed points (called the foci) is a constant. See the picture below. The two definitions are identical. For a circle the two foci are merged into one point at the center.

There are a lot of real world examples of ellipses. Planets orbit the Sun in elliptical paths. The sun is in one of the foci points. The orbits of other stellar objects and satellites are also elliptical. Charged particles follow elliptical paths within magnetic fields. Elliptical patterns are observed in the rotation of ocean currents, elliptical models and algorithms are used in medical imaging, computer science and encryption. Also whispering galleries.

Hyperbola

Comets and spacecraft that are not orbiting another body, in other words, they have enough speed to escape the gravitational pull and continue into deep space, will travel along a hyperbola. The boundary of a shockwave from a supersonic jet (a sonic boom) creates a hyperbolic curve on the ground as it moves. The intersection of two sets of concentric ripples in water makes a hyperbola. The light beam from a lamp or flashlight makes an ellipse or an hyperbola on a plane depending on the angle.

Newton’s Law of Gravitation

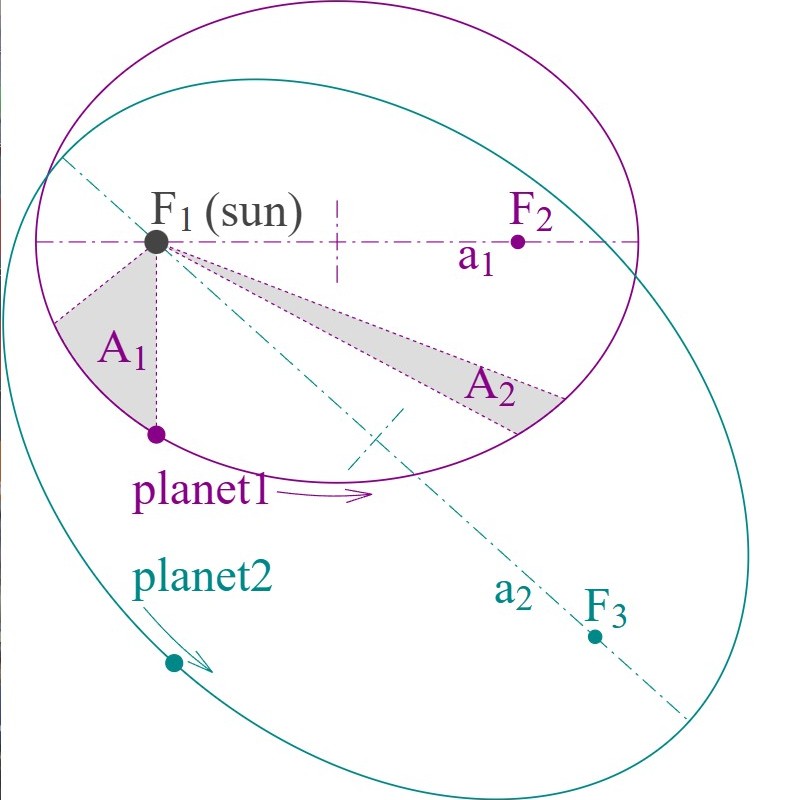

Johannes was an early 17th century German mathematician who derived three laws that describe how planetary bodies orbit the Sun using the observational data collected by the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. The three laws are the following:

- Planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun as a focus.

- A planet covers the same area of space in the same amount of time no matter where it is in its orbit.

- A planet’s orbital period is proportional to the size of its orbit (its semi-major axis).

The orbits are ellipses, with foci F1 and F2 for Planet 1, and F1 and F3 for Planet 2. The Sun is at F1.

The shaded areas A1 and A2 are equal and are swept out in equal times by Planet 1’s orbit.

The ratio of Planet 1’s orbit time to Planet 2’s is (a1/a2)^3/2

Hankwang, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Later Isaac Netwon would use Kepler’s three laws to derive his law of gravity. Newton showed that an inverse-square force (gravity) directed toward the sun was necessary to explain the orbits.

My Other Responses to Esther’s Prompts

- Prompt : Small : Small Microscopic Subatomic and Strings

- Prompt : Kind : Leonbergers Are Kind Dogs

- Prompt : Charge : Electric Charge is not the only type of Fundamental Charge

- Prompt : Promises : Promises To My Dog

- Prompt : Shade : A Total Solar Eclipse the Ultimate Moon Shade

- Prompt : Money : Ten Money Facts

- Prompt : Edge : The Edge of the Observable Universe is 46.5 billion Light Years Away

- Prompt : Fish : Ten Amazing Fish Facts

- Prompt : Promise : I Promise Not to Post AI Generated Comments

- Prompt : Respect : Respect your Dog

- Prompt : Giving : Leonbergers Giving Gifts to Pugs

- Prompt : Family : Dogs Are Family

- Prompt : Snow : Snow and Ice in Norrland

- Prompt : Red : The Universe has a Redshift and its Increasing